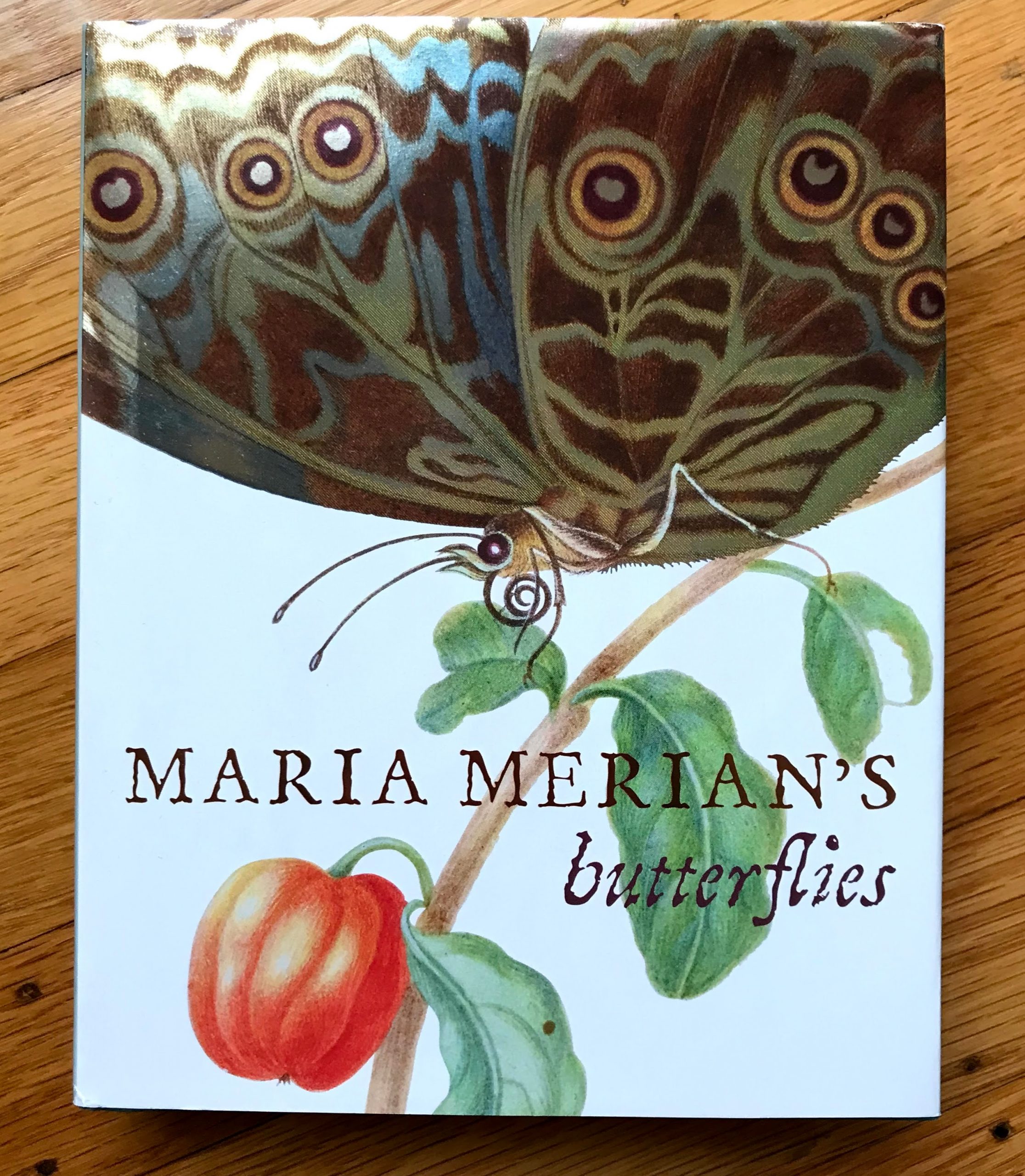

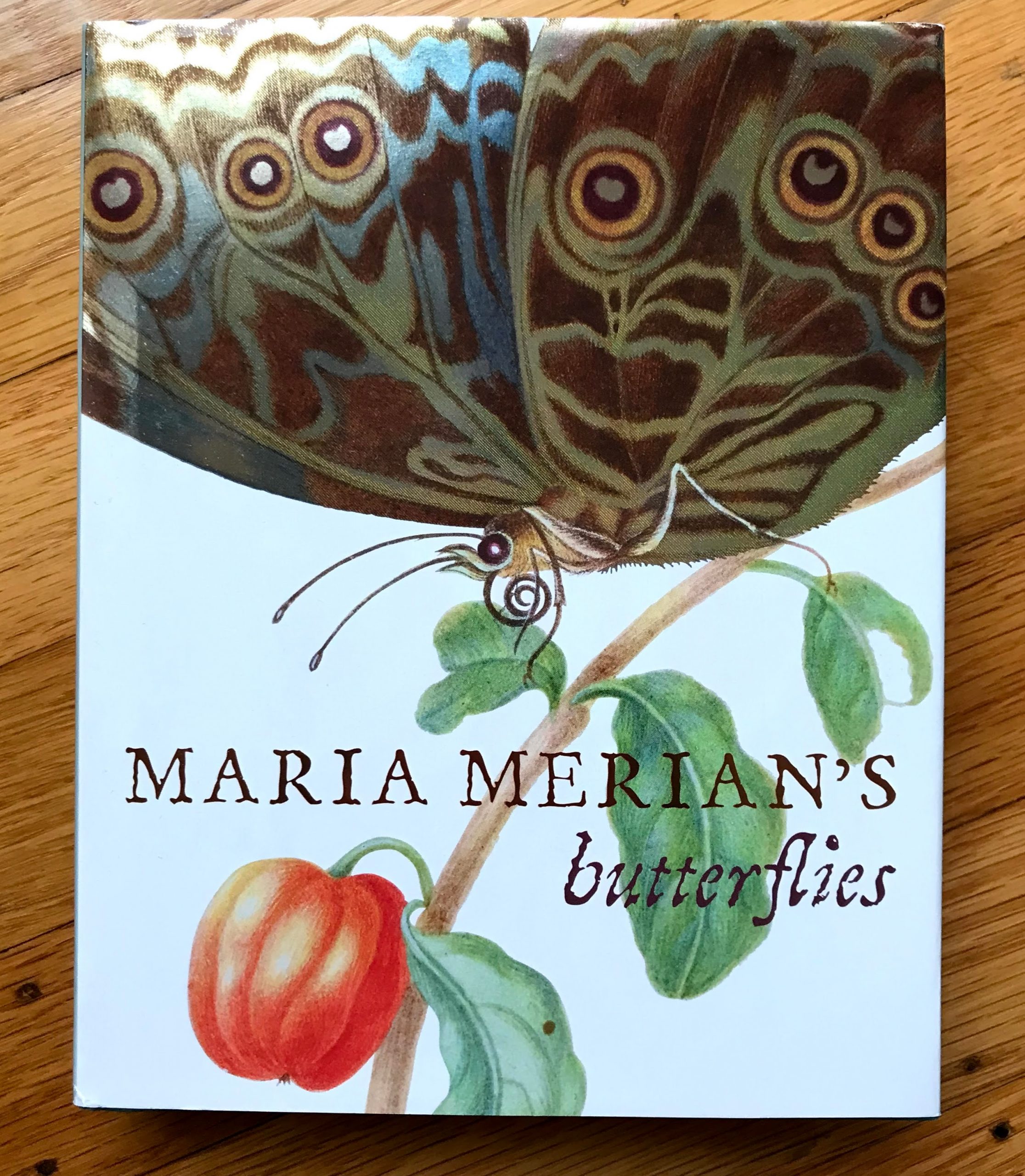

Maria Merian’s Butterflies

by Kate Heard

published by Royal Collection Trust

2016

I LOVE scientific illustrations – they are a glorious combination of art and science! I received a postcard with a gorgeous botanical illustration on it by Maria Sibylla Merian, and decided I needed to learn more.

This remarkable illustrator was born in 1647, and devoted her life to the study and documentation of insects, along with the plants they feed on. She became fascinated by insects at age 13, and studied them throughout the rest of her life. Her father and stepfather both made their living by painting; she taught young girls (including her daughters) to paint, and her painter husband (one of her stepfather’s former apprentices) helped her publish her first book on entomology of local (northern European) insects. After several complex life changes, she wound up selling most of her possessions and taking one of her daughters to a Dutch colony in Suriname to study insects in their natural environments. That trip provided the content that she developed into the publications that became her major life’s work, which were collected by scientific societies, royalty (which is how this book came to be published by the Royal Collection Trust), and wealthy amateurs.

It’s not ONLY that she was a remarkable observer, or that she could draw and paint: she also had to master printing arts to be able to sell editions of her work (printmaking is another skill set entirely), and business to sell different variations of the results at different price points (discounted advanced subscription prices, higher prices after publication; uncolored prints for one price, prints hand-colored by her and her daughters for a higher price, and painted variations on vellum for luxury editions…) . She also collaborated with a botanist to provide in depth information about the included plants.

While this little book is just about 6×8″, the printing is on heavy stock and of high quality. Not only are her plates shown in their entirety with their original titles, but there are many pages of details, so you can enjoy the precision and skill of both her drawing and coloring. It’s the color and detail excerpts that really pulled me in.

The book covers her early work, as well as her work in Surinam. (Note that, while she was born in Germany, she lived in Amsterdam, and the colony she visited was under the control of the Dutch at that time. There is a lot of discussion now about the meaning of the “Dutch Golden Age,” especially since so much of the wealth of Amsterdam was generated by exploitation (the death rate of Dutch sailors working for the Dutch East India Company was shockingly high), colonialism, and slavery. It’s good that this concept of whose hard work the country’s success was based upon is ongoing.)

The Royal Collection Trust has images of their copy of her book on Surinam, which I’ll link to here for your enjoyment:

Maria Sibylla Merian travelled in 1699 with her younger daughter to Suriname in northern South America, to study the flora and fauna. The resulting natural history plates were published in Amsterdam in 1705, at her own expense.

I’m delighted with this book. I even inadvertently learned some things about moths! 🙂