Zaha Hadid

by Philip Jodidio

published by Taschen, Köln

2019

Before reviewing this book, I wish to disclose how I feel about deconstructivism, even though Hadid’s work is NOT the old meaning of THAT fad. I trained as an architect and worked in architecture in the late 80s and early 90s. In school, I had a few oppressively modernist instructors (as in the 1950s concept of modern) get very, very excited about abstract deconstructivist drawings of spaces which could not be built, and which had no human use. While they obsessed over floating red triangles, they still insisted that an ideal building was a Palladian villa. I’m not kidding. They couldn’t see where the movement was going. Also, the deconstructivist works they liked best could not be built on earth because of gravity. They completely missed the rebellion against simple forms that these fetishized, sharp drawings offered. Their enthusiasm for drawings with no application on earth put me off all such work for a long time. In the meantime, Hadid’s real world, mature work displays great characteristics which were implied by her early rebellion against simplistic geometries, which led me to this book.

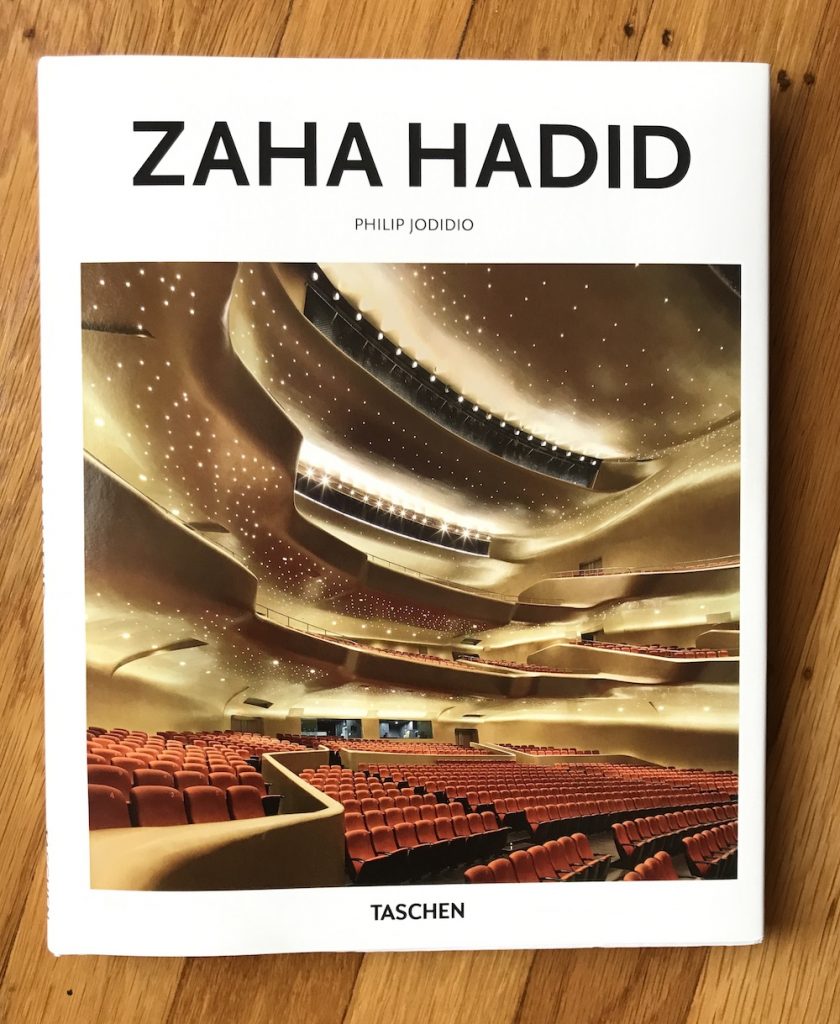

This book is a profile of Zaha Hadid’s architectural practice, and the work of the global firm she founded, which continues to produce remarkable buildings consistent with her approach beyond her death. The Taschen Basic Art series is a collection of artist profile teasers, which get you started in your studies without committing you to a vast, oversized portfolio the size of your coffee table. It takes a light, greatest-hits touch, which was just right for me to familiarize myself with her recent work and help me overcome my misgivings around the early conceptual drawings I used to associate her with.

The essay by Jodidio is long, but it helped me clarify elements of her designs I like. I was pleased to read that she always worked with engineers up front, not at as an afterthought, which explains her innovative designs for walkways (such as the famous floating ramps and stairwells of the National Museum in Rome, and so many other cores of her buildings), which define many of her interiors for me. She incorporated and used below-grade spaces as essential spaces within her designs more visibly than many of her contemporaries, and this allowed for different circulation patterns, which also feel innovative. Her use of organic, fluid-appearing forms carries through her designs in a way I feel is superior to some of the others working on similar projects. Many of her theoretical drawings and early designs also anticipated computer-supported fabrication, so it sometimes feels like the technology caught up with her ideas.

The selection of projects is excellent, and the photography is well done, especially with respect to night scenes and interior lighting. (Hooray for architectural photography!)

I’m not entirely sold on all of the interior spaces. There are walls that melt down into the floor in a way that will tempt skateboarders, but foil pedestrians, and while those feel consistent with the intentions for the overall building forms, they sometimes look… leftover? I’ve been in her building in Seoul, and loved her plazas and bridges, but the interior spaces I entered were more cavernous than comfortable.

This book is an attractive and affordable introduction to the built work of an innovative architect whose portfolio feels both contemporary and futuristic.

For those of you who drink: the introductory essay creates an opportunity for a drinking game. Take a shot each time you encounter the words “seamless” or “chthonic.” You are also allowed to have an outburst each time a comparison to modernism is made.